The History and Culture of the

Central Whidbey Historic District

Canoe Pullers on Penn Cove.

Photo courtesy of Island County Historical Society, Janet Enzmann Archives

Longhouse at Monroe Landing. Photo courtesy of the Island County Historical Society.

Native Peoples: The Lower Skagit

For over 10,000 years, Central Whidbey Island has been inhabited by humans.

The Lower Skagit have long called this place their home, with several permanent villages rimming Penn Cove.

The Northern half of Whidbey Island was historically considered Skagit territory, with their population based primarily around the shores of Penn Cove and the Oak Harbor area. This area was, and still is, teeming with a large variety of plants and animals to support a sizeable community of active hunters / gatherers. The great abundance of food and the calm waters of Penn Cove made this area an excellent location for the “Canoe People” of the Salish Sea.

Čoba?álšjd the village at Snakelum Point is the location of the first village of those of “Pure Skagit” lineage; a sacred place, where many Skagit People believe the Creator placed the first Skagit people.

In 1855, Washington's first Territorial Governor, Isaac Stevens collected the marks (“X”) of Tribal representatives in the Territory to validate treaties, requiring Indigenous Peoples to surrender virtually all their lands to the U.S. Government. In exchange, the tribes were promised money, tools, food, and education for their children. The treaty pertaining to this area is known as the Point Elliot Treaty, signed on January 22, 1855, at Point Elliot, Muckl-te-oh (Mukilteo). Tribal leaders were unhappy with the terms of the treaty, but ultimately consented with what they believed to be the best option for their people – and their survival. The treaty established the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community reservation for the Lower Skagit, Samish, Kikiallus, and Swinomish people, and is located across Swinomish Channel from La Conner. The Tulalip Tribes Reservation, near Marysville is home for several tribes, including the Snohomish, from South Whidbey Island.

One by one, the former villages around Penn Cove were vacated, and the structures were burned or fell into disrepair. The last of the Lower Skagit People in Central Whidbey Island, Alex Kettle & his family, lived in Coupeville until his death in 1947. Alex and his family are the only known Lower Skagit People buried in marked graves in Coupeville's Sunnyside cemetery. Markers for other tribal members were gathered up and burned or rotted away.

NOTE: Before incorporating land acknowledgements in your communications or programs, it's important to ask yourself why you are doing this and to consult with affiliated Tribe(s). This is an incredibly important issue and must be handled with care.

Exploration, Vancouver and the Donation Land Law

In 1792, when George Washington was president of the United States, the kings of both England and Spain sent explorers to chart and claim the Pacific Northwest. Britain’s Captain George Vancouver and Spain’s Bodega y Quadra could have gone to war in their pursuits, but instead, they worked together to chart the Salish Sea.

Captain Vancouer named Whidbey Island in honor of Lieutenant Joseph Whidbey, who explored the island in 1792. Vancouver's well-publicized exploration of Puget Sound helped prepare the way for white European settlers to the region, and the subsequent displacement of the Lower Skagit people from their ancestral lands.

An era of more visible claims to the land began in 1850 with passage of the Donation Land Claim Act and the signing of the Point Elliot Treaty in 1855. The Donation Land Claim Act promised “free” land in Oregon Territory to anyone who could occupy and cultivate the land for four years - regardless of the Indigenous People who occupied the land for thousands of years. As westward-migrating settlers quickly staked claims to the fertile prairies and began farming, the Indigenous People who for centuries utilized the fertile land to grow and harvest camas and berries, were forced from their homelands and through the Point Elliot Treaty signed in Mukilteo, and moved off the island.

Both Isaac Ebey and Samuel Crockett were two of the first to make a claim to the land with their arrival on Whidbey Island. The patchwork of farm fields and roads you see today mark those original Donation Land Claims. Property descriptions today still bear the names of the Donation Land Claim settlers. The Indigenous People became part of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community located in LaConner, Washington.

The protected urban landscape of Ebey's Landing reflects the multitude of people and voices who have left their mark. Explore some of the stories of those living here during the Territorial Period (1850-1889) and interact with maps by clicking the image above.

The Ebey Family

Colonel Isaac Neff Ebey was among the first of the permanent settlers to the island. Upon the advice of his friend Samuel Crockett, Ebey and Crockett came west from Missouri in search of land. Both men had filed donation claims on central Whidbey by the spring of 1851. Ebey wrote home, enthusiastically urging his family to join him.

Ebey's family soon emigrated to the island. The simple home of Isaac's parents, Jacob and Sarah, and a blockhouse erected to defend their claim against Indians, still stand today overlooking the prairie that bears the family name. As for Isaac, he became a leading figure in public affairs, but his life was cut short in 1857, when he was slain by northern coastal Indians seeking revenge for the killing of one of their own chieftains.

Today some farmers of Central Whidbey still plow donation land claims established by their families in the 1850s. Their stewardship of the rich alluvial soil preserves a historic pattern of land use centuries old.

Fertile farmland was not the only incentive to settlement. Sea captains and merchants from New England were drawn to the protected harbor of Penn Cove and the stands of tall timber valued for shipbuilding. Many brought their families and took up donation claims along the shoreline. One colorful seafaring man was Captain Thomas Coupe, who startled his peers by sailing a full-rigged ship through treacherous Deception Pass on the north end of the island. In 1852, Coupe claimed 320 acres which later became the town of Coupeville on the south shore of the cove.

The early success of central Whidbey's farming and maritime trade transformed Coupeville into a dominant seaport. The past remains apparent in Coupeville today, with its many 19th-century false-fronted commercial buildings on Front Street, its historic wharf and blockhouse, and its rich collection of Victorian residential architecture.

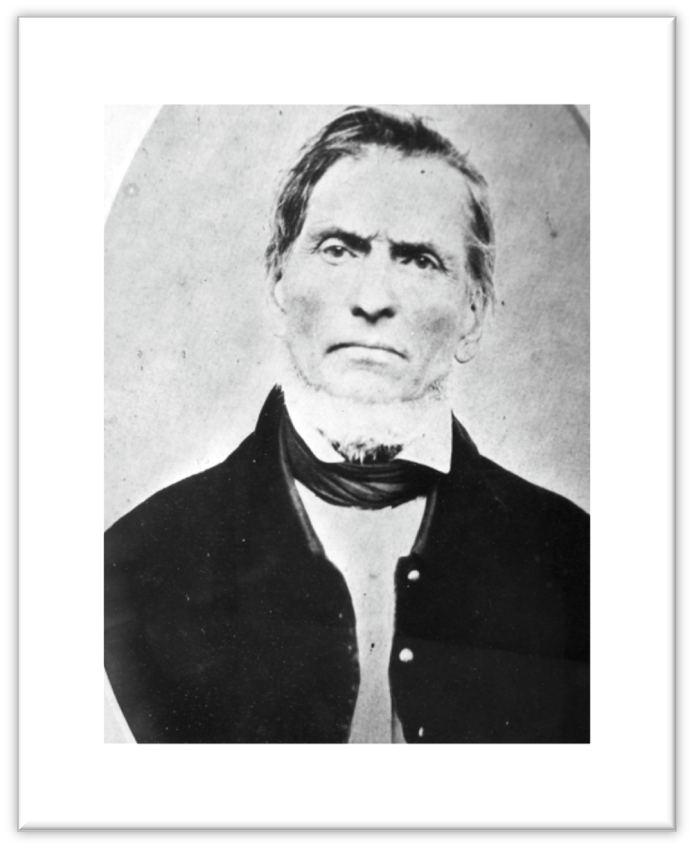

Jacob Ebey

Jacob and Sarah Ebey, like many other settlers, travelled across the country on the Oregon Trail, ultimately landing on Whidbey Island in 1856 to join his son Isaac Ebey. Their claim, called Sunnyside, is located on the ridge above Ebey’s Prairie, with views of Admiralty Inlet and the Olympics.

Col. Isaac Neff Ebey

Isaac Ebey, son of Jacob & Sarah Ebey, and his close friend, Samuel Crockett, made their way across the country and eventually to Whidbey Island. Isaac and his wife, Rebecca claimed 640 acres of what is called Ebey’s Prairie. Ebey’s Landing National Historical Reserve is named for Isaac Ebey.

Winfield Scott Ebey

Son of Jacob & Sarah Ebey. Much of early settler life is documented through Winfield’s prolific journals. Following Isaac’s tragic death, Winfield, along with cousin George Beam, built the iconic Ferry House in 1860 as a source of income for Isaac’s two sons, Eason and Ellison.

Mary Ebey Bozarth

Mary Ebey Bozarth travelled with her parents, Jacob and Sarah Ebey, across the Oregon Trail to her new home on Whidbey Island. Mary founded Sunnyside Cemetery on her father’s Donation Land Claim, where the family rests together.

Most of the names of the Chinese farmworkers in the Reserve were lost to time. However, the center image is of a man named Ah Soot who came to the United States in 1880. Ah Soot is buried in Sunnyside Cemetery in the LeSourd family plot.

Images of documentation photos are held at the Island County Historical Society, Janet Enzman Archives.Museum.

The Chinese in the Reserve

Between the 1880s and the 1920s, Whidbey Island was home to a Chinese community centered on Ebey’s Prairie. The island became a destination for Chinese laborers seeking their fortune, and escaping unrest in their homeland. Some Chinese were smuggled into the country, however most came legally through the immigration station in Port Townsend. They worked as farmhands for local white families or rented land to grow their own crops, particularly potatoes. Their labor was critical tot he prairie’s agricultural development and they were welcomed by the farmers who leased land to them.

Beginning in the 1890s, the Chinese became targets of expulsion campaigns by local merchants. Anti-Chinese hostility included boycotts against renting farmland to Chinese tenants, dynamiting their stored potatoes, and shooting at their residences.

From the Island County Times, October 12, 1900.

The Chinese community resisted by taking up arms, drawing upon the legal and political resources of nearby Chinese communities & Chinatowns, and enlisting the support of sympathetic white neighbors and employers. While the Chinese were never forced off the island, racist hostility, exclusionary immigration laws, and time all took their toll. By the late 1920s, the last aging Chinese residents of Ebey’s Prairie had moved to urban Chinatowns, returned to China or died.

“Do not touch the magic stick to the white man’s paper! We do not know what the white man has written on that paper!

Let him sign his own paper, that is his paper, not ours.”

Our interpretations of the past continue to evolve, and as they do, we will make every effort to make sure these are included in our messaging from our website to printed materials. We are all stewards of the past and stewards of the future.